Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are restricted by law to purchasing single-family mortgages with origination balances below a specific amount, known as the “conforming loan limit” (CLL) value. Loans above this amount are known as jumbo loans.

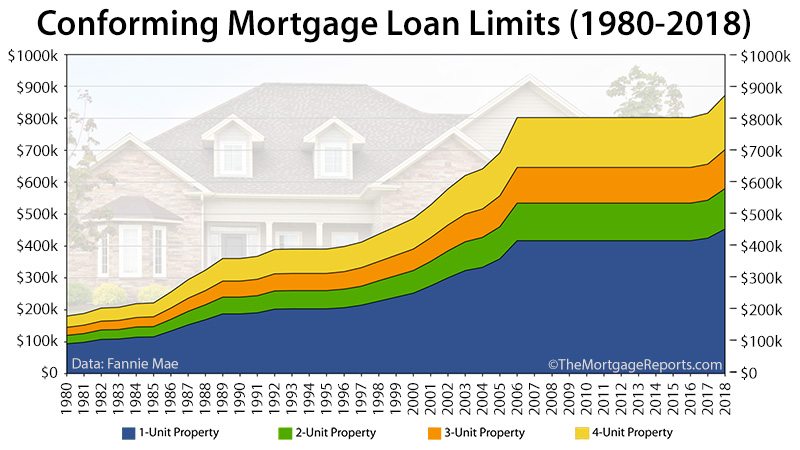

The national conforming loan limit value for mortgages that finance single-family one-unit properties increased from $33,000 in the early 1970s to $417,000 for 2006-2008, with limit values 50 percent higher for four statutorily-designated high cost areas: Alaska, Hawaii, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Since 2008, various legislative acts increased the conforming loan limit values in certain high-cost areas in the United States. While some of the legislative initiatives established temporary limit values for loans originated in select time periods, a permanent formula was established under the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 (HERA). The 2024 conforming loan limit values have been set under the HERA formula.

Conforming loan limits have an interesting history, undergoing many changes since being established in the 1970s. These limits play a key role in the mortgage market by setting the maximum loan amount that can be purchased by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Tracing their evolution provides insight into housing finance policy over the decades.

What Are Conforming Loan Limits?

Conforming loan limits set the maximum original loan balance for mortgages that are eligible for purchase by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Loans above the limits are called “jumbo loans” and do not meet the GSEs’ guidelines. The limits vary by number of units, with higher limits for 2-4 unit properties.

Fannie and Freddie are restricted by their charters to buying loans below the conforming limit. This aims to focus their activities on serving moderate-income borrowers rather than higher-end housing.

Origins in the 1970s

Conforming loan limits were established as part of the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation Act that chartered Freddie Mac in 1970. This set an initial limit of $33,000 for single-family homes.

The limit sought to focus Freddie Mac’s purchases on modest homes catering to low- and moderate-income borrowers. The relatively low $33,000 threshold reflected typical home prices at the time.

Fannie Mae became subject to the same limits after being converted to a GSE in 1968 Previously the limits did not apply to Fannie as a government entity.

Rising to Meet Higher Prices: 1970s to Mid-2000s

As home values increased over the decades, conforming loan limits gradually rose to keep pace. This allowed Fannie and Freddie to maintain a presence in the conventional market.

The limit doubled to $67,500 by the end of the 1970s. It surpassed $100,000 for the first time in 1981 and then reached $153,100 by 1986.

Incremental increases continued in the 1980s and 1990s. The Housing and Community Development Act of 1987 indexed limits to the annual change in average home prices.

By 2006 the baseline limit for a one-unit property hit $417,000, over twelve times higher than the original level. Conforming loans still represented a majority of the market due to the steady limit increases.

Introducing High-Cost Area Limits: Early 1990s

In the early 1990s, legislation created increased limits for designated high-cost areas. Alaska, Hawaii, Guam and the U.S. Virgin Islands received limits 50% above the baseline.

This aimed to keep conforming loans relevant in higher priced markets. Homes in these areas would have quickly exceeded a one-size-fits-all national limit.

Temporary Stimulus Expansions: 2008 Onward

The 2000s saw the limits remain flat at $417,000 as policymakers debated GSE reform. But starting in 2008, a series of temporary expansions tripled the limits in many counties to over $1 million.

These stimulus increases were enacted to support the struggling housing market after the subprime mortgage crisis. They enabled larger jumbo loans to be sold to the GSEs.

The Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 brought the first expansion. Others followed in stimulus bills over the next several years on a temporary basis.

The HERA Formula: Factoring in Home Prices

In 2008, the Housing and Economic Recovery Act (HERA) established a permanent methodology for setting limits based on local median home prices.

Currently the baseline limit is set at 65% of the conforming loan limit for a metro area. County limits cannot go below the floor or above the ceiling set by FHFA.

This data-driven approach indexes limits to home values on an ongoing basis. It replaced the former fixed limits that required legislation to change.

Recent Trends and Future Outlook

The HERA formula has governed limits since 2009, providing stability but less policy control. The limits fell slightly after stimulus programs ended but are rising again amid home price growth.

There is periodic debate about reforming the limits or transitioning to private capital. But for now, the limits remain a key pillar of the US housing finance system. Barring major GSE reform, conforming loans will continue playing a central role for the foreseeable future.

In conclusion, conforming loan limits have continually adapted over the decades to balance market stability and policy goals. Their growth reflects rising home values while new approaches try to index limits based on local prices.

Limits have progressed far beyond 1970s levels through gradual increases and temporary stimulus expansions. It will be interesting to see how they continue evolving in the future as housing finance policy adapts to changing economic conditions. The limits remain a key mechanism that shapes the mortgage marketplace.

2024 Conforming Loan Limit Values

Conforming Loan Limit Values for Calendar Year 2024 — All Counties

History of Mortgage Industry

FAQ

What was the conforming loan limit in 1997?

|

Year

|

One Family ($)

|

Three Family ($)

|

|

1997

|

214,600

|

331,850

|

|

1996

|

207,000

|

320,050

|

|

1995

|

203,150

|

314,100

|

|

1994

|

203,150

|

314,100

|

Why did conforming loan limits increase?

What was conforming loan limit in 2009?

What is the conforming loan limit for 2011?